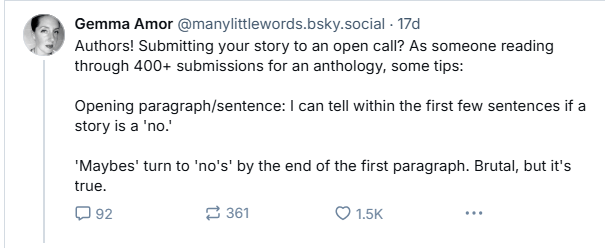

A few weeks ago, I was scrolling through my BlueSky feed (@ianjskidmore.bsky.social) when I came across a post from someone I wasn’t following at the time, which made me stop:

I clicked through onto Gemma’s post and started looking at the replies. I was surprised, and bit disturbed, at the number of posts from bskyers who were offended by her advice. It seems that a fair few contributors felt it was unfair of her to triage her submissions in the way she described: surely everyone submitting for her anthology is entitled to have their piece read completely before being rejected? It made me consider how much my own book-browsing habits mirrored what Gemma was describing: how far through page one do I read before deciding not to follow the author through the gate?

There are some books where the opening line jumps out at you: “Call me Ishmael”; “It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.” I should confess that I’ve never read either Moby-dick or A Tale of Two Cities, but that doesn’t invalidate the fact that both Melville and Dickens were right on the money when it came to getting a prospective reader’s attention.

Here are two more examples of cast-iron opening sentences from authors I have read, and whose works have influenced me greatly:

“It was the day my grandmother exploded” were the first words of Iain Banks I ever saw; I still have the paperback copy of The Crow Road which introduced me to Banks’s worlds, created both with and without the M in the middle. I was more affected by his premature death than I realised at the time. I struggled to find a contemporary writer whose books could compete with Iain’s; for a long while, I regressed to re-reading the authors I’d discovered in my twenties and thirties. That’s still a habit I struggle to break, and which is now causing problem as I try to identify suitable comps for my own novel, but at least I can continue to look forward to new work from William Gibson and Neal Stephenson.

The other opening line I‘ll quote here is from a book I would have chosen to read even if it hadn’t been a set text at school:

“In a hole in the ground, there lived a Hobbit.” I was twelve when I was introduced to Bilbo Baggins and his domestic arrangements. The rest of the opening paragraph drew me into Tolkien’s imagined world; its cadences are so beautifully balanced that it was used by our Voice tutor, Sue Cowan, during one of the workshops she delivered when I was privileged to study acting with some of RADA’s teachers back in the Nineties. I remember my delight at finding a hardback copy of The Fellowship of the Ring in the school library, followed soon after by despair at the realisation that the corresponding editions of The Two Towers and The Return of the King were not available to be borrowed (I soon purchased a paperback edition which comprised all three volumes, long since discarded through being loved not wisely, but too well). Nowadays there are hardback editions of most of Tolkien’s work, as well as his son’s complimentary volumes, on the bookshelf in my workroom.

So having a killer first line is critical, right? Not necessarily… As Gemma asserts, however, often “’maybes’ turn into ‘noes’ by the end of the first paragraph.” She’s discussing this in the context of curating 400+ submissions for an anthology, but it’s true of long-form fiction as well. I’ve lost count of the number of samples I’ve downloaded to my Kindle which haven’t been converted into full-manuscript requests for one reason or another. Perhaps I didn’t get on with the authorial voice; perhaps the story’s premise didn’t agree with me; or perhaps I just didn’t care enough about the protagonist by the end of the first few pages.

That being said, some of the authors whose books I’ve repeatedly returned to over the years don’t start out with a strong first couple of paragraphs.

Chapter one of Julian May’s The Many-Coloured Land doesn’t really hint at what’s to come; it reads like a romance between Mercedes and Brian, which wasn’t something I was looking for when I first picked it up in 1983. Yet I found myself re-reading The Saga of the Exiles and the Galactic Milieu Trilogy in their entirety forty years later.

Similarly, Robert Holdstock’s Mythago Wood might be discarded as a war memoir on the basis of the first two paragraphs of chapter one. It’s not until Holdstock quotes from Steven Huxley’s father’s journal towards the bottom of the page that the substance of the story is hinted at. When I had to choose a noveI to analyse for my first assignment when I took my MA in Creative Writing at Nottingham Trent in 2010, I chose Holdstock’s book. What’s interesting to me as a writer is the fact that the opening section was something Holdstock dashed off in a hurry because he needed something to share at the next meeting of his Writer’s group.

[I should mention, for the sale of full disclosure, that both The Many-Coloured Land and Mythago Wood open with a prologue. There’s a completely separate debate to be had about the role of the prologue in popular fiction, but that’s for another post on another day].

On balance, then, it seems that Gemma’s advice is sound: I need to grab my reader’s attention within the first few words, certainly by the end of the first page, if I want them to keep reading. How successful am I at this? In my next blog, I’ll give you the chance to decide when I discuss my own WIP, The Witch of Islay.

Leave a comment